Church Practices, Church Polity, and Cooperation: How Baptist distinctives in theology and at church form the basis for healthy multi-church cooperation

Editor’s note: this article appears in the Fall 2021 issue of Southwestern News.

The practices and polity of the church are fundamental to Christianity. Specifically, they are fundamental to faithful discipleship, to cooperation with likeminded churches, and to denominational integrity.

Ecclesiology is the name given to the area of theology that includes the practices and polity of the church. Interest in ecclesiology has been growing in recent years.

Our Baptist forebears championed these distinctives, not just in their own churches, but also in their associations, even at the cost of criticism and ridicule from other Christians who did not agree. We would do well today to learn from their examples.

Ecclesiology is Fundamental to Discipleship

God purposed to establish His church from the beginning. The church was not a parenthesis in the plan of redemption. It had a central role in God’s eternal purposes.

Paul directed most of his epistles to churches. Those written to Timothy and Titus chiefly concern church affairs. Christ addressed the responsibilities of His churches in the seven letters of Revelation 2-3. Christ commissioned the apostles to establish churches in accordance with His plan for their government, officers, worship, ordinances, membership, discipline, and work. The church is “God’s household,” Paul told Timothy, “the pillar and foundation of the truth” (1 Tim. 3:15).

Christ established a certain polity and certain practices in His churches. Obedience to Christ required Christians to join with other believers in forming churches with scriptural polity and practices. Every Christian had a duty to the church and a duty to act as part of the church. Baptist churches have generally expressed these duties in a “church covenant.”

The Atlanta First Baptist Church adopted its covenant in 1848. Like those of other Baptist churches, the covenant expressed their members’ acceptance of Christ’s authority over them individually and corporately—“to do all things whatsoever the Lord hath commanded us to do.” Members pledged to support the doctrines of the Bible and the practices that Christ required of His churches. They pledged to support the worship, not neglecting to gather together, as well as supporting the ministry of the Gospel, upholding the ordinances according to Scripture, and practicing church discipline. They promised to submit to Christ and to His church. “Holding ourselves henceforth to be [H]is and no longer our own,” they pledged to separate from the world and be a church, “each esteeming himself henceforth as a member of a spiritual body, accountable to it and subject to its control.” Following Christ faithfully included obeying His commands to the churches.

Ecclesiology is Fundamental to Cooperation

Christ’s commands to the churches required them to cooperate and New Testament churches cooperated. Cooperation was practically necessary to attend to an array of duties since churches need one another’s aid effectively to defend truth, oppose error, address difficulties, resolve differences, and above all, to obey the command to make disciples of all nations. Cooperation, however, was difficult unless churches had wide agreement regarding theology and ecclesiology. Matters of minor difference called for charity and generosity. But, disagreement on fundamental matters of theology and ecclesiology hindered cooperation because it would require some to endorse beliefs or practices that they could not in good conscience endorse.

Agreement in theology and ecclesiology was, therefore, necessary to sustain cooperation. Baptists called this area of fundamental agreement our “faith and practice.” “Faith” referred to the doctrines that Christ required the churches to believe and teach. “Practice” referred to the polity and practices that Christ required the churches to observe.

Agreement in theology and ecclesiology, therefore, has been a condition of cooperation throughout our history. When Baptist churches in Georgia organized the Sarepta Baptist Association in 1799, they adopted a statement of doctrine and of church practices as the basis of their union. Since some Baptist churches existed “who differ from us in faith and practice, and it is impossible to have communion where there is no union, we think it our duty to set forth a concise declaration of the faith and order upon which we intend to associate.”

Associations, therefore, refused to admit churches into their union unless they could affirm their agreement with doctrine and ecclesiology of the member churches. They examined every church that applied for membership. They followed the pattern of the Charleston Baptist Association in 1785 when the Stephen’s Creek Church applied for admission: “Upon a satisfactory account of their faith and practice, resolved, [w]e are willing to receive them into union with us.”

Baptists viewed ecclesiology as an essential basis of our cooperation with one another.

Ecclesiology is Fundamental to Denominational Faithfulness

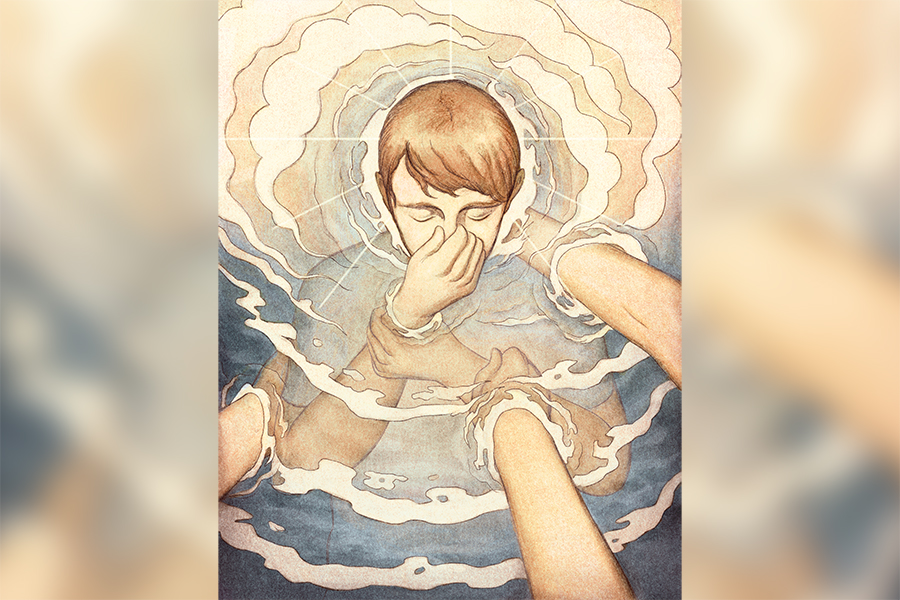

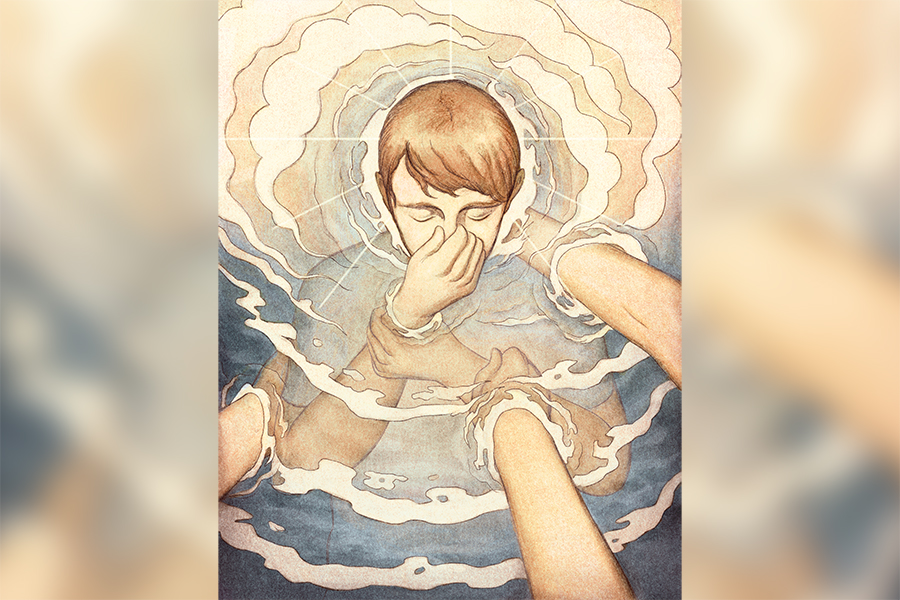

Baptists often faced pressure to relax or ignore elements of our faith and practice since some persons have viewed our doctrines and church practices as offensive. We taught that those only who were born again, having confessed their sin and sought Christ’s mercy, may be baptized. We also taught that baptism was immersion by definition. Hence persons baptized as infants or by sprinkling were in fact unbaptized.

We affirmed that baptism was prerequisite to participation in the Lord’s Supper. Non-Baptist denominations affirmed the same requirement. However, since we did not recognize infant baptism or any non-immersion as valid baptism, we could not in good conscience invite such persons to the Lord’s Supper, since they lacked an essential qualification.

We affirmed that the entire membership of each local church had joint responsibility for obedience to Christ’s commands to the churches. The congregation, therefore, had ultimate authority under Christ in the administration of all His laws in the church. We held that Christ required His churches, by an exercise of this congregational responsibility, to expel from the church body any members who disobeyed Christ’s commands and refused to repent. Such church discipline offended many people. Baptist churches practiced faithful church discipline for nearly three hundred years.

Baptists recognized that many of their fellow citizens found their views and practices objectionable. Even some Baptists took offense. Rufus C. Burleson, whose ministry shaped early Texas Baptists, urged his fellow Baptist pastors in 1849 to teach the broad set of truths and practices which Christ required His churches to believe and observe. Some preachers refrained from insisting on the fundamental convictions reflected in our confessions because to do so would hinder church growth. Burleson acknowledged that “it will repel from our church those persons who hold loose and erroneous views of doctrine, and our numbers, and sometimes our wealth, will thereby be decreased.” But, large numbers did not mean great strength. “We grant that our numbers for a while will be lessened by adhering rigidly to the old landmarks, but we are fully assured that our real strength will be greatly increased.”

Burleson argued that some preachers retreated due to fear of criticism, ridicule, and rejection. They refrained from advocating our fundamental convictions because “contending for our doctrines will diminish our popularity, and expose us to persecution. This, we fear, has more influence, even upon Baptists, than we suppose. But could our venerable fathers arise from the dead, or speak to us ‘from under the altar’ (Rev. 6:9), what would be their language? What would be the words of the Waldenses, of a Roger Williams, an [Obadiah] Holmes, a [John] Bunyan? Should we not hear them exclaiming: ‘For these principles, we suffered exile, the lash, the stake, the dungeon—and will you desert them for a little breath of popular applause?’”

Our teachings and practices can give offense. If we teach and observe them, we may drive some people away. We will unavoidably invite ridicule and scorn upon the church. We must be charitable, generous, and loving to those who differ from us. If, however, Christ has revealed what beliefs the churches must teach and what practices the churches must observe, then we have no alternative but to seek to lead our churches to teach and practice these things. If obeying Christ’s commands gives offense, we prefer faithfulness to the Lord over popularity.

Unity and cooperation in fulfilling Christ’s commission cannot long endure on any other basis than agreement to teach and practice what Christ requires of us. The faith and practice revealed in Scripture form the true basis of our denominational union. Biblical church practices and polity are fundamental to our union because they are fundamental to our faith.

Gregory A. Wills is research professor of church history and Baptist heritage and incoming dean of the School of Theology (effective Jan. 1, 2022) at Southwestern Seminary.