A LEGACY OF SOUL-WINNING: Carroll doubts his preaching skills, but God’s Word shines through

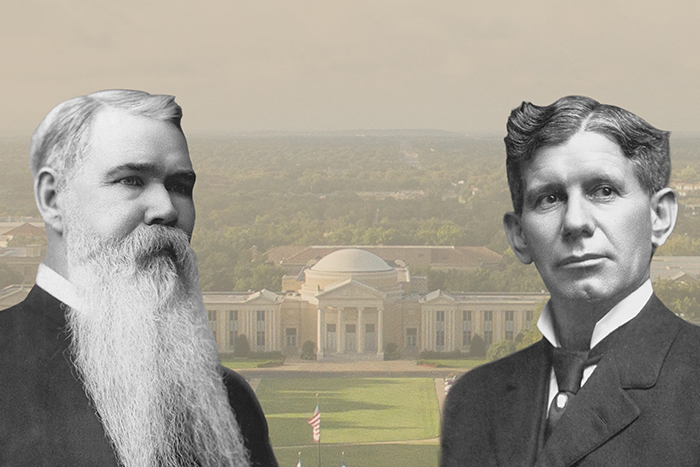

Editor’s Note: The following is part of an ongoing series examining the evangelism experiences of significant figures from Southwestern Seminary’s history. This story is taken from Dr. B.H. Carroll, The Colossus of Baptist History, a compilation of the observations of J.M. Carroll, brother of Southwestern founder B.H. Carroll, and others.[1]

Almost immediately after his baptism, B.H. Carroll began to build a reputation as a fiery and persuasive preacher. He held fruitful revivals and opened a Sunday School. He became known for his skills, but on one occasion, when he believed that he had fallen short of his objective, his confidence took a nosedive. But he should never have lost faith.

“One night, he preached what some of us thought was a mighty sermon,” J.M. Carroll recalls. “The preacher evidently did his best, but no move was made. No one professed; no one even went to the mourner’s bench.”

B.H. Carroll felt that he was to blame. “He wondered why somebody was not saved,” J.M. Carroll writes. “He always expected that to happen at every service. What a night of agony for the preacher!”

B.H. Carroll was restless that night, and did not sleep. He sighed and groaned and wrung his hands all night, his brother recalls.

“I was greatly distressed,” J.M. Carroll writes. “I thought he was bad sick. I frequently went to him. He would say to me, not with crossness but more with sadness, ‘Go away, Jimmie. Go to bed. You can’t help me.’”

The spirit of distress hung thick in the house. Occasionally, the preacher would call out, “O God, have I been mistaken in my call? Am I not to preach? Am I dishonoring Thy cause?”

His misery prevailed all night, and by morning, he had not slept. He refused breakfast. The workday started, but he would not leave his room, and his brother was afraid to leave him alone. “I was not then a Christian,” he writes. “I could not understand.”

Then, around 9 a.m., relief arrived in the form of a young man who approached the Carroll home on a horse. “It was Clark Hilliard,” J.M. Carroll writes, “considered the hardest sinner in the whole neighborhood. Probably not that he was worse in morals, but careless and thoughtless of religion.”

No sermon had ever seemed to touch him, Carroll writes. Hundreds of prayers from relatives and friends had gone up for him, “but he seemed to have a heart of stone.”

Hilliard called out to Carroll: “Jim, is your brother at home? … May I see him?”

J.M. Carroll took Hilliard to B.H. Carroll’s room. “What a pitiable sight he was,” Carroll writes. He told his brother that Hilliard had asked to see him. Without interest, B.H. Carroll lifted his head and asked, “What is it you want?”

Hilliard responded, “I was out at preaching last night and heard your sermon—I cannot get away from it. I never slept last night. I am a lost sinner. I have come to you for help.”

The change was momentous. The once-distressed preacher leaped out of bed and said, “Let’s pray.”

“The two knelt, and I bowed my head,” J.M. Carroll writes. “Such a prayer! He first asked God to forgive him for his lack of trust, and then asked God to save the young man.”

All three individuals were radiant with happiness. “It was one of the great meetings in the life of B.H. Carroll,” his brother writes.

Carroll took this encouraging turn of events as a reaffirmation of his call. Following that revival, he began another meeting, then another. And as it happens, J.M. Carroll came to know the Lord during one of those meetings under B.H. Carroll’s preaching.

[1]J.W. Crowder, ed., Dr. B.H. Carroll, The Colossus of Baptist History (Fort Worth, Texas: J.W. Crowder, 1946), 81-82.