A LEGACY OF SOUL-WINNING: Trifling unbeliever ‘shocked’ from disbelief

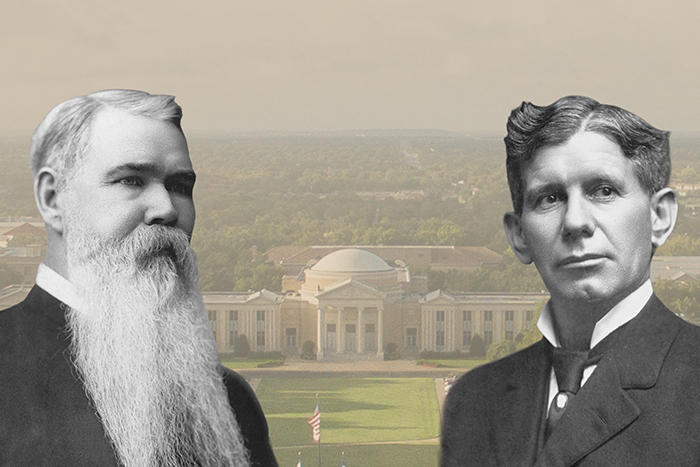

Editor’s Note: The following is part of an ongoing series examining the evangelism experiences of significant figures from Southwestern Seminary’s history. This story is taken from chapter 28 of With Christ After the Lost, written by Southwestern’s second president and namesake for both Scarborough College and the seminary’s Chair of Evangelism, L.R. Scarborough.[1]

Early in the ministry of L.R. Scarborough, a “young, high-spirited professional man” gathered several Christians around him and asked what Scarborough calls “infidel” questions—that is, those intended to challenge their faith. The man laughed as the group responded with confusion and uncertainty.

Scarborough approached the group, and the man said, “Let’s try this young preacher and see if he can help us out.”

As Scarborough walked into the group, the man asked him his question. But Scarborough did not answer. Instead, he put his hand under the lapel of the man’s coat and said, “Your trouble is not your infidelity. You are living a double life, untrue to your wife and deceiving her and your friends; but you are not deceiving God. Be sure your sins will find you out.”

Then Scarborough immediately left without further discussion. The man became angry, swore, and “raged that the preacher had insulted him,” Scarborough recalls.

Scarborough met with the man three days later, after “he had cooled off and was in his right mind.” The man said to him, “I wanted to whip you—and would, if I had seen you. I was first mad at you, then at myself, and then at the devil.”

“I want you to pray for me,” the man said. “You have discovered me. I want to be a Christian.”

“It was not long until he was saved, and since that time, he has lived a consistent Christian life,” Scarborough says.

This evangelism method is classified by Scarborough as the “shock” method. It is one of two means identified by Scarborough by which evangelists may deal with a “light-headed, trifling disbeliever.” An evangelist may shock him with “God’s hammering word” or convince him by the “purity, genuineness, and strength of your Christian life.”

Scarborough cautions that the former method is a dangerous one to use, for “it is easy to make a mistake and do it in a wrong spirit.” Even so, he affirms it as an effective means for confronting “trifling” unbelievers with their sin.

On another occasion, Scarborough faced another trifling unbeliever, this one a young college senior. In this case, however, the “shock” method was unnecessary, for God had used another means to beckon him to draw near.

In a conversation with Scarborough, the senior said, “I can answer all the arguments you have made for Christ’s deity, the inspiration of the Bible, the efficacy of Christ’s death, but I cannot answer my mother’s life. I want you to pray that I may have what she has, that which made her what she is.”

“The logic of a great life for God cannot be answered,” Scarborough says. “… Life won where logic failed.

“A mother, a wife, a child; a godly businessman; a doctor, lawyer, or farmer, pure in life; a deeply spiritual preacher—these may win to Christ by their walk with God and their purity of life. This is a fine method to try on all kinds of sinners.”

Regarding whether to “shock” or simply to “convince,” Scarborough says that evangelists must “seek the wisdom of God for guidance as to which will be the more effective.” Ultimately, he said, Christians must be careful to see all unbelievers “in the light in which Christ saw them when He died for them. … Put God’s value on men, and you will long to see them right with God.”[2]