Something worse than persecution? ‘Yes!’ say two Nigerian Baptist leaders

Editor’s note: This story originally appeared in the fall 2020 issue of Southwestern News. On Dec. 7, the U.S. State Department added Nigeria to the list of “Countries of Particular Concern” under the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 for engaging in or tolerating “systemic, ongoing, egregious violations of religious freedom.”

More Christians have been martyred in Nigeria in the last year than any other country in the world, except Pakistan.

But compartmentalized and nominal Christianity are greater threats to the Christian faith in the west African nation than persecution by notorious Boko Haram terrorists and other Islamic militants, according to two Nigerian Baptist leaders who face the threat of persecution every day.

Not that they diminish in any way the deep, ongoing, and growing opposition faced by Christians in Nigeria, especially in the northern part of the nation. Indeed, many experts on Christian persecution have raised alarms about the nation, including governmental entities like the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) and the U.S. State Department. Others have urged the United States to declare Nigerian Christians victims of genocide. Nigerian President Mohammadu Buhari reported in September that even President Donald J. Trump confronted him in a 2018 Oval Office private meeting with the jarring question: “Why are you killing Christians?”

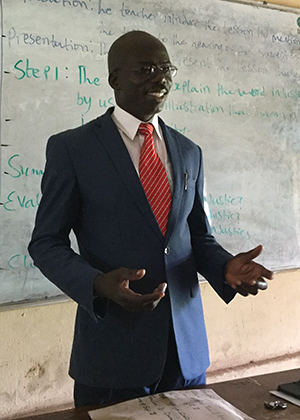

David Dagah and Moses Audi—both Southwesterners—live and work on the borderland between Nigeria’s Christian-identifying south and the Muslim-dominated north where persecution is not a theoretical issue; it’s a daily threat. Yet, these two Baptist leaders are as deeply concerned about the problem of compartmentalized and nominal Christianity in their nation—Christians who are more influenced by the culture around them than Christ who lives in them; those who profess the Christian faith merely because they live in a region dominated by Christianity but allow traditional African religions to influence their daily lives as much or more than the Bible; “Christians” by virtue of the professed faith of their parents but who reject Christ’s teachings of love for enemies.

Dagah, a Ph.D. student in Southwestern Seminary’s World Christian Studies (WCS) program in the Roy J. Fish School of Evangelism and Missions, and Audi, a 2016 Ph.D. graduate of the same program, have focused their academic work on strengthening the evangelical commitments of Nigerian Baptists and other Christians so that the transformative power of the Gospel will allow their countrymen to properly face the challenges of persecution and evangelize their nation— especially in the Muslim north.

Nigeria is the largest economy in sub-Saharan Africa, with a heavy reliance on oil as its main revenue, according to the CIA World Factbook. Boasting Africa’s largest population at more than 203 million, about 53.5 percent identify as Muslim, and 45.9 as Christian. Nigeria is bordered by the nations of Benin, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon, and the Atlantic Ocean, and in land mass is approximately 1.4 times larger than the State of Texas.

The nation became known in recent decades for severe persecution of Christians by Islamic militants, most notoriously those associated with Boko Haram, which has identified itself with the Islamic State and been designated a terrorist organization by the U.S.

“The church in Nigeria, particularly in the north, is presently under siege by the forces of darkness,” says Dagah, a third-year Ph.D. student. “Murderous attacks on religious and ethnic minorities are going on daily unabated” with ineffective intervention by authorities.

Both Dagah and Audi note that not all attacks on Christians are truly persecution for their faith, with complex economic, cultural, tribal, and historical factors playing a role as well. Nevertheless, “It is no gainsaying that Christians are being persecuted in Nigeria,” Dagah says.

In 2000, Islamic terrorists destroyed by fire Baptist Theological Seminary Kaduna (BTSK), where Audi serves as president and Dagah serves on faculty. The Islamic radicals were attempting to close down the Baptist school in Kaduna state, where the majority of the population is Muslim. In recent years, while persecution has intensified, seminary leaders have begun rebuilding the seminary in a safer location further south in Kaduna City, although most of the school’s operations remain in the Muslim-dominated area. Approximately 500 students are enrolled in the seminary.

Dagah, who has pastored six Baptist churches and served for 10 years as president of the Kaduna Baptist Conference of about 600 churches (similar to a state Baptist convention in the Southern Baptist Convention), says Christians are persecuted in many ways: denied land to build church buildings, children are denied certain educational opportunities, public positions are off-limits, Christian facilities—including church buildings—are destroyed, women and girls are forced to convert and marry Muslim men, forced relocation from Muslim-dominated areas, and murder. Dagah says “tens of thousands” of Christians have been slain by Islamic radicals in his country, an estimate consistent with findings of USCIRF.

While Dagah’s direct family members have not experienced severe persecution, “many of my relations, friends, and church members have suffered different degrees of persecution; some have even lost their lives,” he says.

An example of the kind of brutal persecution of Christians in Nigeria came at Christmastime in 2019 when an offshoot of Boko Haram released a video that received worldwide attention in which 10 Christians and one Muslim were executed. A few months before, the same group released a video showing the beheading of two Christian aid workers. By some estimates, more than 150 Christians were martyred in just the first six months of 2020.

The problem of Christian persecution in Nigeria is so great that USCIRF has asked the U.S. State Department to declare the nation a “country of particular concern”—a formal designation under U.S. law for nations “engaging in or tolerating systematic, ongoing, and egregious violations of religious freedom,” according to its annual report this year. Meanwhile, Baptist Press reports that a number of organizations—Christian Solidarity Worldwide, Christian Association of Nigeria, International Christian Concern, the Colson Center for Christian Worldview, and the Jubilee Campaign for Religious Freedom—have called what’s happening to Christians in Nigeria “genocide.”

In the midst of these difficult realities, however, Dagah sees a greater threat to Christianity in Nigeria.

“My most profound worry is not about the persecution, but the church’s response to it,” he says. “It is apparent in the New Testament that Christians will be persecuted. The church’s response to persecution in Nigeria has not been according to biblical standards: love, prayers, and witnessing for the transformation of lives. This is a significant concern for me.”

Dagah is writing his doctoral dissertation on the compartmentalization of Christianity among Ham Baptists—his native people of Nigeria. While 96 percent identify as Christian, there is “glaring” compartmentalization of “beliefs and practices between Christianity and traditional religion,” which hurts the “transforming power of the Gospel in their lives and their culture,” Dagah says.

“Compartmentalization of religion, therefore, is dangerous and needs to be checked,” he adds.

Dagah says that Southwestern’s WCS program is helping him address the problem of compartmentalization by articulating the problem, creating awareness of the problem among the Ham people because of his interviews with their leaders about the matter, and guiding him as he teaches students at BTSK to help them understand and address the issue in their ministries.

“The heart of the Gospel—Good News—is the transformation into Christ’s image,” he says. “I believe the awareness and help given to students and others to deal with religious compartmentalization will, by and large, have a rippling effect.”

Dagah says Fish School faculty have modeled for him how he should fulfill his teaching responsibilities.

“The way they related to us as brothers, friends, and co-laborers is simply incredible. I have learned the best way to relate to my students in humility from the Roy Fish faculty.”

John D. Massey, Fish School dean, says WCS “allows students from around the world to research Christian communities in their respective fields of service. Students examine the history of those communities, their current state, various societal and cultural challenges to being the church in their unique localities, and the theological issues they face.”

Currently, there are 23 students enrolled in the program, with 11 nations represented, including Madagascar, Germany, Cuba, Egypt, Indonesia, and a number of other countries that cannot be listed for security reasons.

Dean Sieberhagen, Vernon D. and Jeannette Davidson Chair of Missions, notes that westerners, including some International Mission Board missionaries, are also enrolled in the WCS program. “We do not extract them for four-plus years and have them residential on our campus but rather require them to stay in their ministry context and pursue their studies via Zoom for seminars and mentor tutorials,” he says. “… This approach keeps them fully engaged in their local context and ministry.”

Massey says the “library” for the students “is the Christian community they are examining in an intensive and academic manner,” and the WCS program “spotlights the global nature of Christianity and interprets it through an evangelical lens.”

The evangelical commitment of the program and of Southwestern Seminary is vital, according to Audi, who encouraged Dagah to enroll because of his own experience with faculty dedicated to “sustaining evangelical Christianity,” he says. “The evangelical voice is an imperative for our time. I am proud to be associated with Southwestern Seminary for upholding the biblical revelation across the span of their ministry influence.”

Audi adds that Dagah’s studies at Southwestern will encourage him to “continue with evangelicalism at a time when new theologies are in a battle for supremacy in the life of the church.” He says their student population comes with “some of these varying theologies,” citing aberrant examples like prosperity teaching and liberation theologies. “I believe his training at Southwestern will further encourage him to stand for biblical Christianity over against other contending theologies.”

While persecution is “inevitable” in the Christian life, Audi says “it takes a truly converted individual to respond biblically,” noting the inadequacy of nominal Christianity.

Audi, whose 2016 doctoral dissertation focused on a Christian response to Boko Haram, says too many Nigerian Christians are responding to persecution by withdrawing from the mandate of the Great Commission, and nominal Christians are susceptible to false teaching, including those who justify violence against Muslims as an appropriate response to persecution.

“A response characterized by love, continued witness, and discipleship, which is the only road to victory, is increasingly neglected,” he says. “Here lies the greatest challenge facing the church in Nigeria.”

For more about Nigerian Baptists’ response to persecution, see Audi’s article “Missions and Insurgency in Nigeria: A Historical Survey of Nigerian Baptist Convention Work, 1980 to 2020 and the Future of World Christianity” in the spring 2019 issue of the Southwestern Journal of Theology.