SWJT article examines ‘lost legacies’ of Truett, Criswell on race, racism

The “lost legacies” of George W. Truett and W.A. Criswell regarding matters of race and racism in the Southern Baptist Convention are examined in an article of the spring issue of the Southwestern Journal of Theology, the academic journal of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. Written by O.S. Hawkins, president of GuideStone Financial Resources, the article is among eight essays exploring the journal’s theme of “The Doctrine of Humankind.”

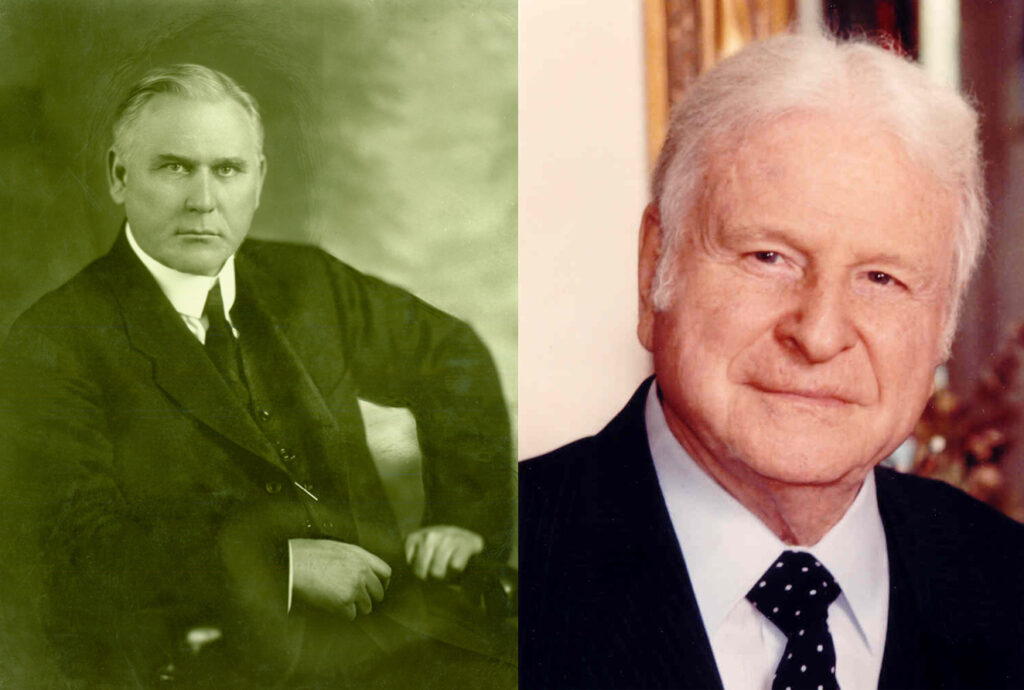

Truett and Criswell each pastored the First Baptist Church of Dallas, Texas, in the 20th century, and Hawkins is among their successors. Both men are highly regarded figures within the SBC, each having significant and fruitful ministries, and both are honored by Southwestern Seminary. While Criswell is honored with a lobby named for him in MacGorman Chapel, Truett’s 36-year affiliation with the seminary as a founding trustee and president of the board for 13 years, is recognized through Truett Auditorium and Truett Conference Room in the B.H. Carroll Memorial Building and by the George W. Truett Chair of Ministry, an endowed professorship currently held by David L. Allen, distinguished professor of preaching.

Nevertheless, Hawkins’ article reveals that Criswell strongly advocated segregation in his early career, a position of which he later repented, and Truett failed to speak out against the racism present in his congregation. Truett served First Baptist Dallas as pastor from 1897 until his death in 1944, while Criswell served the church from 1944 until his death in 2002 as pastor, senior pastor, and pastor emeritus. Both men also served as SBC president—Truett, 1927-1929; Criswell, 1968-1970.

“O.S. Hawkins deserves our gratitude and praise for his research on this important matter concerning Southern Baptist history, which is interwoven with our beloved seminary’s history,” said Adam W. Greenway, president of Southwestern Seminary.

“Like some of our most cherished heroes of the Bible, who at times committed scandalous acts because of their sinful natures, we must be honest enough to acknowledge that some of our Baptist heroes were guilty of sins of omission and commission that are grievous,” Greenway added. “Unlike today’s cancel culture that seeks to erase historical figures who failed in some aspect of their lives, we can all be grateful God did not cancel sin-scarred saints like Abraham, Moses, David, and others who trusted in God’s grace—and that He also does not cancel present-day believers who fall short of God’s glory even as they sincerely seek to walk with Jesus.”

In his journal article, Hawkins reported that Truett never publicly spoke out against the Ku Klux Klan, even as leaders and others in his own church were closely associated with the iniquitous secret society. Also, while Truett led the board of trustees at Baylor Hospital in Dallas, which he had played a key role in founding, African American doctors were not permitted to practice medicine at the hospital.

Meanwhile, Criswell would ultimately regard his 1956 address before the joint session of the South Carolina General Assembly passionately defending segregation as “one of the colossal blunders of my young life.” In 1968, Criswell preached a sermon declaring the church open to all races—“one of the defining addresses of his life,” Hawkins wrote.

In an interview reflecting on the journal article, Hawkins said that Truett’s relationship to the race issue came to his attention while he served as pastor of the Dallas church, 1993-1997, and he started “delving into the history of our great city.”

“I came upon the fact that the Ku Klux Klan’s largest cell in 1921 in America was in Dallas, consisting of 13,000 members,” he said. “I further discovered the names of its 100-member steering committee. Upon seeing them, I found in our church rolls that the names of an alarming and significant percentage of this steering committee came from Truett’s diaconate and church membership.”

Much of Hawkins’ research for this article is related to his new book, In the Name of God: The Colliding Lives, Legends, and Legacies of J. Frank Norris and George W. Truett, published by B&H Academic and scheduled for release on Sept. 1, along with its sequel, One Somebody You: The Life and Legacy of W. A. Criswell, which will be released next year.

Hawkins noted that “giants of the faith” like Truett and Criswell “dwindle into more ordinary men the more we know about them.” He added, however, that “we should not put asunder other good they may have done to the benefit of the expansion of the Gospel. We are all sinners, and all walk on feet of clay.”

Hawkins explained that Truett’s racial sins “were more those of omission than of commission, more of what he did not say and do than what he said and did.” Still, Truett’s voice, “above all others,” could have made a difference in the racial issues of his day, but he was “sadly virtually silent” while members of his own church leadership were on powerful committees of “the most vile and demeaning organization in our nation’s history.”

“By almost every other measure, George W. Truett lived a life of impeccable integrity and enjoyed in life a level of respect few have known,” Hawkins said. “… He built so many worthy and God-honoring things that have lasted, and when he spoke, people had a unique way of doing what he suggested.

“All of his goodness should not be laid aside in a day when some are seeking to cancel out everything related to anyone whose life had its own shortcomings and sins. As Scripture states, ‘Let him who thinks he stands take heed lest he fall’ (1 Corinthians 10:30).”

Hawkins, a two-time alumnus of Southwestern Seminary, including earning the Doctor of Philosophy degree last year, concluded, “The fact that many of our Southern Baptist forefathers—from Boyce to Broadus to Baylor and a multitude of others, who achieved so many good things and built institutions that have lasted over the decades—could be so blind to their own sin and to their own reading of Scripture related to racial issues remains one of the imponderables of Almighty God.”

On how Christians today can reconcile the “good with the bad” in the case of such men, Gregory A. Wills, research professor of church history and Baptist heritage at Southwestern Seminary, said, “Christian heroes were sinners all. Not one was perfect. We do them and the Gospel a disservice when we ignore their sins and errors. It dishonors the Gospel also to ignore their virtues and faithful service. We ignore neither side of their contradictions.”

“We should grieve on account of their sin, but we should not be surprised that they were sinners,” added Wills, who also serves as director of the B.H. Carroll Center for Baptist Heritage and Mission. “In the case of slavery and racism, Christians and churches sinned on a profound scale as they embraced the deep-rooted false principles of the world. We do not condone their sins or exonerate them. We emulate them only so far as they emulated Christ Jesus.”

Hawkins’ article is one of eight in the spring issue of the SWJT exploring the doctrine of humankind. Other topics include an explication of the image of God, what it means to be created male and female, a Christian understanding of human sexuality, the significance of the human body, and questions regarding transhumanism and artificial intelligence.

SWJT editor and Southwestern Seminary interim provost David S. Dockery wrote in his editorial that Hawkins’ article is complemented by an essay by Carl J. Bradford, assistant professor of evangelism at Southwestern, on a “Gospel-centered approach” to race, racism, and the importance of racial reconciliation.

“I am hopeful that scholars and students as well as pastors and church leaders will find the current publication to be a valuable resource for the days to come,” Dockery wrote.

The spring 2021 issue of the Southwestern Journal of Theology is available online here.